On July 4, 1966, at his estate 60 miles east of Austin, Lyndon B. Johnson savored his Independence Day holiday by helicoptering around his sprawling Hill Country ranch; lunching with a federal judge, the president of Neiman Marcus, and two lawyers; boating around a Colorado River reservoir named in his honor; and placing two late-night calls to Defense Secretary Robert McNamara.

But the most historically significant event that holiday didn’t merit a mention in the president’s daily diary. Sometime that summer day in the Texas heat, Johnson reluctantly appended his signature to what he called “the f—ing thing”: S.1160, a bill for which Rep. John E. Moss, a fellow Democrat from Sacramento, Calif., had agitated for a decade. No ceremony accompanied the signing. The New York Times, the next morning, ran its coverage of the new law on page 25.

Signed that day, the Freedom of Information Act, a landmark bill which opened up executive branch records to public inspection, nearly didn’t pass. Johnson, known for his controlling personality, had privately regarded the act with suspicion. To make his hesitations known, Johnson instantly undercut the law with a signing statement — the first in a long tradition of presidents undermining FOIA, a legacy that continues through the Obama administration today, who recently tried to beat back minor fixes to FOIA’s inadequacies.

A Backbencher’s Crusade

In April 1965, 15 months prior to the signing, LBJ had dispatched the House Democratic leadership to kill the proposed FOIA legislation before it could get out of subcommittee. LBJ saw in it a conspiracy to take down his administration with scandals. According to his press secretary Bill Moyers, LBJ “hated the very idea of open government, hated the thought of journalists rummaging in government closets, hated them challenging the official view of reality.”

Rep. Moss, on the other hand, had fought government secrecy for years, first during the Eisenhower administration, when he tried to figure out why 3,000 federal employees, likely pinkos, had been purged. After 11 more years of pointing out “silly secrecy,” like the government’s refusal to say how much peanut butter American soldiers ate, Moss had come to believe “the unfortunate fact [is] that governmental secrecy tends to grow as government itself grows.” Eventually, Moss’s tenacity, the touchstone book “The People’s Right to Know” (1953) by Harold Cross, testimony from prominent newspapermen, plus the full-throated arguments of a second-term Illinois Republican, Rep. Donald Rumsfeld, solidified a strong vote in the House.

After the vote, the FOIA languished on Johnson’s desk for 10 days. One more, and it could have been pocket-vetoed while Congress was adjourned for the summer. LBJ, however, surprised even his closest advisers by signing it, without ceremony, in July 1966. White House staffers quickly drew up a press release that enumerated the bill’s limitations — military secrets, whistleblower complaints, personnel files, an agency’s internal communication and, lastly, the President’s own files were off-limits — while also extolling the public’s right to know. Johnson found the statement too praiseworthy, and he personally limited its scope. The draft of his statement had said that the mistakes of public officials should “always [be] subjected to the scrutiny and judgment of the people.” Johnson cut the line. In its place, he added that the “desire of … private citizens” should not determine what records are made public or kept private.

From that date on, the right to know about our government’s doings has been under near-constant attack, besieged in federal courtrooms, bureaucratic offices and Congressional backrooms. Secrecy, after all, had long its advantages, which public officials weren’t eager to relinquish.

The New FOIA

Fifty years later, public information is still cloaked by black-out redactions and years-long delays. (The oldest pending FOIA request, at the National Archives and Records Administration, dates back to August 1993.) To be fair, the government is digging itself out of a 103,000-case backlog at the same time it’s receiving a record numbers of inquiries: 713,168 requests last fiscal year. But Rep. Simon Chaffetz, a Utah Republican who chairs the powerful House Oversight and Government Reform committee, says that’s no excuse. “The power of FOIA as a research and transparency tool is fading,” committee staff concluded in a damning report earlier this year. “Members of the media described their complete abandonment of the FOIA request as a tool because delays and redactions made the request process wholly useless for reporting to the public.”

To confront the challenges, on June 30, shortly before Barack Obama celebrated his last Fourth of July in office (with a Janelle Monáe and Kendrick Lamar concert in the White House’s East Room), the president signed an update to the FOIA. (Besting Johnson, but not by much, Obama spoke about the bill for 107 seconds before he inked his signature.) The FOIA Improvement Act of 2015, a rare piece of bipartisan legislation sponsored by Sen. John Cornyn, a Texas Republican, was an attempt to fix half-century-old inadequacies and won support from dozens of oversight groups, including the American Civil Liberties Union, the Society of Professional Journalists, and the Sunlight Foundation.

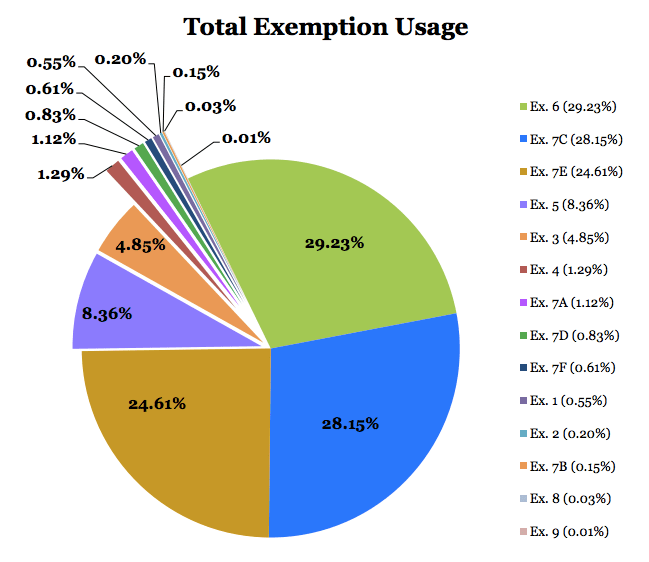

The law’s most important change added explicit direction about the law’s purpose: FOIA officers and judges should presume documents can be released unless they can point to an explicit legal prohibition or a chance of causing harm. Ideally, the statutory exemptions should now work as they were originally intended: not as catch-alls onto which denials can be hung, but as guides to balancing individuals’ privacy, the country’s national security and government efficiency with accountability to its citizens.

The change settles an unresolved question that, in recent years, has swayed with each new presidential administration. In October 2001, a month after 9/11, George W. Bush’s attorney general, John Ashcroft, vowed to defend every FOIA denial in court unless a denial was clearly illegal. (Aschroft was rebutting a 1993 directive from Bill Clinton’s appointee, Janet Reno, demanding discretionary materials be released.) Permanently overturning Ashcroft’s guidance, the new law locks into statute a proclamation that Obama issued on his first full day in office. “To usher in a new era of open Government,” the president wrote in January 2009, FOIA ”should be administered with a clear presumption: In the face of doubt, openness prevails.” That means, as then-Attorney General Eric Holder reiterated in March 2009, that the Department of Justice would not defend discretionary withholdings in court. Amidst the flip-flops, Congress’s clarification of FOIA’s purpose should prove valuable if the next presidents wishes to limit transparency. And given the choice between Donald Trump, who forcefully removes journalists from campaign events as payback for negative articles, and Hillary Clinton, who hasn’t held a single press conference this year, probably due to questions about her private email server, that could come in handy in five months.

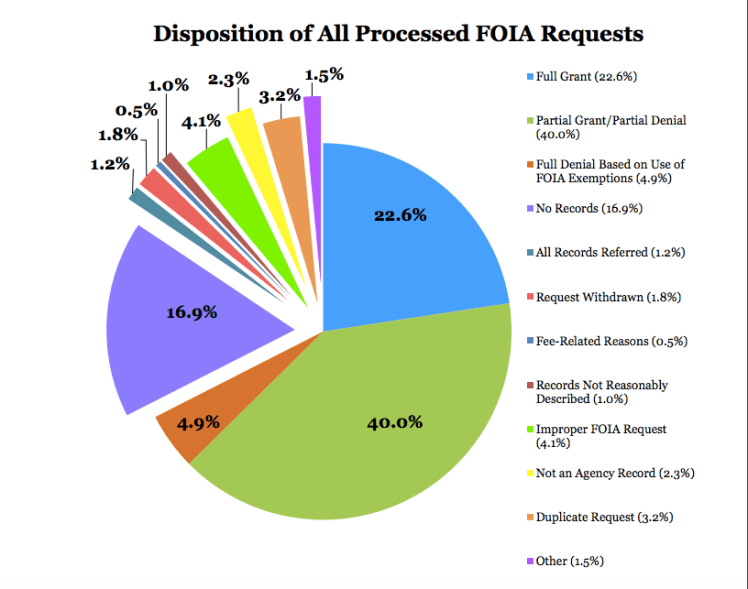

But cynics will tell you the presumption of openness won’t do much; indeed, Holder’s memo has been in effect for seven years. But only one in five processed FOIA requests were granted in full last year; 498 FOIA lawsuits — a record high — were filed during the same period. (DOJ’s Office of Public Affairs did not immediately respond to questions about when government lawyers had last refused to defend a discretionary FOIA denial.)

To be sure, for a few select media companies with resources to litigate, the newly codified presumption may tip the scales in their favor. But for the general public, there’s little recourse if an administrative appeal of a denial spits back another rejection. (Pro se plaintiffs, who represent themselves in court, can’t recover expenses if they win a FOIA lawsuit.)

Which leads to the new bill’s second big change: the Office of Government Information Services (OGIS), an eight-member team, can now mediate a FOIA dispute between an agency and a requester at any time, will check in on agency compliance and present recommended improvements directly to Congress. The ombudsman, however, lacks enforcement power: OGIS can only foster a sense of cooperation, not demand it.

Other adjustments include sunsetting Exemption 5’s protection of deliberative materials 25 years after a records was created, waiving fees any time an agency misses its deadlines, forcing agencies to proactively post documents online if they’ve been requested three or more times, and tasking the Office of Management and Budget with building a one-stop online request portal that covers all 100 agencies.

Another Attempt to Kill Reform

But what about the backlogs, those denials? The modest improvements passed this year were all previously blocked in 2014. In the waning days of that Congressional session, then-speaker John Boehner held a bill at his desk — identical the one introduced this year — running out the clock despite virtually unanimous support in both chambers.

Who was behind the last-minute impediments? Like in Moss’s day, when the Department of Justice reasoned that FOIA was “unconstitutional,” the agency once again tried to stymie reforms. (Paradoxically, DOJ is tasked with ensuring agencies adhere to the law.) “The [Obama] Administration strongly opposes passage of H.R. 1211” — the House version of the FOIA Improvement Act, S.2520 — the Justice Department privately advised lawmakers in 2013, according to documents the Freedom of the Press Foundation obtained through a FOIA lawsuit. “The Administration believes that the changes proposed in H.R. 1211 are not necessary and, in many respects, will undermine the successes achieved to date by diverting scarce processing resources.”

What was Obama’s team opposed to? For one, they didn’t want to see Holder’s presumption of openness become law. Asking agencies to withhold only documents that “would cause foreseeable harm,” the Justice Department argued behind the scenes, would set up a standard that “effectively amends each and every one of the existing exemptions in a manner that is fatally vague and subjective,” begging for lawsuits and undermining the exemptions’ original purpose. “Removing agency discretion … would create massive uncertainty and would chill intra-governmental communication,” the talking points continued, making it sound as if Holder’s directive hadn’t had much staying power. Even a tweak in the language, to broaden agencies’ discretion, would be insufficient; the presumption should be excised in its entirety, they said.

“If this memo reflects thinking of the White House, than I have to question their commitment to transparency,” Anne Weismann, The Campaign for Accountability’s executive director, told Vice News. “The breadth of their objections and lack of evidence to back up their claims and their absolute opposition to codifying Obama’s memo expose the lie that is the administration’s policy: If the president and this administration believes in their stated FOIA policy they should be supporting an effort to codify it.”

The Justice Department also attacked an expanded role for OGIS, saying added prominence for the ombudsman could “needlessly detract from DOJ’s authority to guide the Executive Branch with regard to FOIA.” Essentially, OGIS would be stepping on the department’s toes. Most worrisome to DOJ would be the direct line OGIS would gain to Congress to issue recommendations. Previously, the Department of Justice had the chance to review — and likely, influence — these suggestions before they were sent to legislators. Preferring OGIS not interfere in its administration, the Justice Department asked that bill’s multiple references to the ombudsman be removed, because they “would unduly burden agencies, create inefficiencies, [and] conflict with the neutrality of a mediator,” they wrote.

Given the scathing opposition the bill faced from the “most transparent administration in history,” its small victories need to be celebrated. Dating back to Johnson, reforming FOIA has always been an grueling undertaking. It took the Watergate scandal to initially add judicial review to FOIA denials (and override Gerald Ford’s veto) in 1974, the revolution of the World Wide Web to make records available electronically in 1996 and recognize online journalists as news media in 2007, and finally, the law’s semicentennial this year for Obama to affirm FOIA’s original intent. Here at On the Records, we’ll keep advocating for true fixes to FOIA — even if it takes another anniversary to get them.